Dawson McAllister’s 1999 book on the Millennial generation is aimed at parents and youth leaders. The title tells us quickly that those parents and leaders are concerned about the emerging generation and culture:

Dawson McAllister’s 1999 book on the Millennial generation is aimed at parents and youth leaders. The title tells us quickly that those parents and leaders are concerned about the emerging generation and culture:

Saving the Millennial Generation: New Ways to Reach the Kids You Care About in Uncertain Times

Dawson came from Peoria, Illionois. He graduated from Bethel College in Minnesota and then studied at Talbot Theological Seminary. While in seminary, McAllister worked as a youth pastor and began a coffee house ministry in the late 1960’s to runaways who had come to Southern California. He founded Shepherd Productions in 1973 to market the manuals he was using alongside his public speaking in schools and conferences. In 1991 he started his talk show, Dawson McAllister Live. He is still active as a radio host.

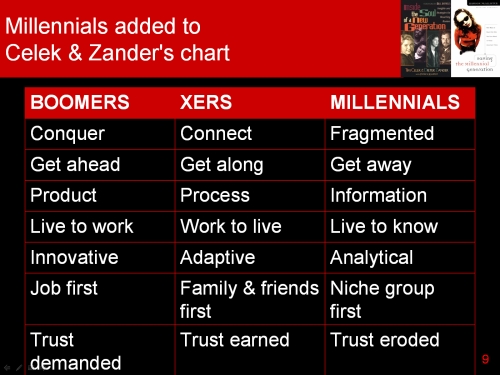

Dawson starts his book writing about his experience of talking with high school students over time, witnessing changes in youth culture. He introduces his readers to the Millennials, the generation that comes next on the chart outlined by Tim Celek and Dieter Zander in their 1996 book, Inside the Soul of a New Generation. (see chart on right) The Millennials, (born 1982 on) would be the high school graduation class of 2000. From his experience Dawson identifies emerging traits of this generation: plugged in, passionately tolerant, spiritual, but without focus, not quick to trust adults, and hard to shock.

Continental Shifts

McAllister goes beyond the generational culture to explore what he calls “continental shifts”. In particular he explores the move toward postmodern and post-Christian perceptions. The Millennials are growing up in a new environment. Parents being more attentive. Education, he observes, has become marked by both “back to basics” and political correctness. Government programs have become more “pro children”.

Dawson explains the growing weakness of institutions by drawing on Strauss and Howe’s “period of unravelling”. The period of unraveling is highlighted in high levels of abortion, growing drug abuse, divorce, teen pregnancy, deepening anger, and an anti-USA feeling in world. This was two years before the September 11 terrorist attacks on the United States. As a citizen of New Zealand, I found the reference to the anti-USA feeling a little disturbing. I grew up with a distrust of American imperialism, a distrust made even deeper by the United States’ refusal to dialogue with New Zealand over its nuclear free policy.

Adolescent Development

Having identified a number of major shifts in societal attitudes, McAllister reminds us that adolescent development is still basically the same. Early adolescents – thirteen to fifteen year olds – still tend towards concrete thinking, black & white, all-or-nothing, have difficulty with ‘why questions’, are self absorbed, and see God in terms of transaction. Older adolescents tend to be less tied to self and derive their identity from affiliation with a peer group. Their thinking is becoming more abstract and reflective. They are more comfortable with ‘why questions’ and are prepared to explore nuances of meaning, looking for a richer and deeper spirituality. God is seen more as approachable.

Youth Culture

McAllister takes us on a tour of youth culture, giving us examples of the corroded values found in music, television, movies, sexual activity, drug use, technology and education. He tells us that trust has been eroded for the Millennial generation. There is a lack of a clear defining purpose that can be picked up by young people. Their role models are all fallen. McAllister’s approach here tends to be alarmist and “glass half empty”. He comes across as someone standing on the outside of a strange and dangerous culture.

McAllister is conerned that online culture is exposing young people to more and more options without developing wisdom. Young people are growing up playing online games, accessing dangerous information, being corrupted by “smut”. The increasing speed of internet connection is leading ironically to prevalent attitudes of impatience and isolationism.

Corrosion of Truth

McAllister at this point expresses his deep anxiety at the corrosion of truth in the emerging generational culture. He sees young people growing up believing that experience is the ultimate measure of meaning. Evangelical, Bible-believing Christians are being regarded as “anti-progress, reactionary, stupid and dangerous”. As an Evangelical, Bible-believing talkback host, he tries to model being a real representative of God who loves passionately, is reasonable and compassionate, but doesn’t shrink back from drawing lines in the sand. Dawson here outlines what he sees as the contemporary battle lines for truth.

McAllister gives his readers three choices in how we respond to Millennials

- Condemnation, which turns people off

- Accommodation, which is not respected

- Empathy – the model of Jesus.

We need to be straight, be real, McAllister says. Young people value experience more than propositional truth. They respond to interviews and encounters rather than lecturing. They need the opportunity to apply scripture in everyday life. The traditional model of youth ministry, focusing on knowledge, communicates content, entertaining and teaching, with a youth minister as hub. The spiritual formation model focuses on intimacy with God and facilitates experience, equipping people to notice, name and nurture God’s hand at work. It’s led by a team of mentors.

Theological Colors

At this point, McAllister reveals his theological approach, “Hold fast to the truth”. He outlines Paul’s experience at Athens in which he engages with a clearly misguided culture. Christ’s resurrection, he says, is the watershed issue. Apologetics are required for a new generation that had little regard for the inerrancy of the Bible. If young people could hear about Jesus and his death on the cross, the Holy Spirit would follow up with the work of truth telling.

McAllister writes on the challenges of discipling the Millennial Generation, helping young people find a meaning that goes beyond entertainment. He cites the mentoring approach modeled by Jesus and Paul. We need competent volunteers who are appropriately vulnerable, experts in affirmation, and actively involved in meeting the needs of young people. We need new heroes for the emerging generation.

Church for Millennials

In his section on church for Millennials, Dawson cites the wisdom of Don Richardson on cross cultural mission. We need to keep to the core truth of the gospel. We should recognise three stages in cross-cultural mission experience: initial enthusiasm, discouragement and adjustment. We need to perservere so that we can find common ground with the Millennials.

Parenting Millennials

McAllister finishes with a chapter for parents of Millennials. Parents need to be more attentive than before, keeping in touch with a wider youth culture, affirming, and avoiding the extremes of control and permissiveness. They would need to practice active listening skills, practicing spiritual formation at home.

Millennials, Dawson reminds us, need adults to model spiritual authenticity, demonstrate intentional direction, and live as genuine mentors and heroes.