Jordon Cooper posted on Rwanda on his blog a couple of times this last weekend. His concern is about the lack of action from the United States and United Nations eleven years ago.

The Rwandan story hit me hard back in 1994. I was visiting at a conference in Dunedin when the news started coming through. World Vision showed a video exposing the extent of the violence. I remember being physically sick in response. The next year I heard the story from a Rwandan Anglican bishop speaking at a NZ Christian leaders conference. I found myself weeping uncontrollably. In 1998 I researched the Rwandan reconstruction for a paper I was writing while studying in San Francisco. I got home to NZ and within months my wife and I became sponsors for a refugee family from Rwanda.

The Rwandan story hit me hard back in 1994. I was visiting at a conference in Dunedin when the news started coming through. World Vision showed a video exposing the extent of the violence. I remember being physically sick in response. The next year I heard the story from a Rwandan Anglican bishop speaking at a NZ Christian leaders conference. I found myself weeping uncontrollably. In 1998 I researched the Rwandan reconstruction for a paper I was writing while studying in San Francisco. I got home to NZ and within months my wife and I became sponsors for a refugee family from Rwanda.

Here’s the paper on reconciliation I wrote in 1998…

A Rwandan woman is credited with refusing to name the killer of her husband, in the aftermath of the genocidal massacres of 1994. “This is enough”, she says. “This killing has to stop somewhere. One murder does not justify another killing. We have to break the cycle of violence and end the genocide.” (1) The process of reconciliation in Rwanda will have to address this woman’s concern, and more. The recalling and healing of painful memories will need to be placed alongside the development of a will to live in a multiracial society, with new narratives of community. International and local expressions of sorrow, responsibility and repentance will need to be placed alongside symbolic gestures of forgiveness and new beginnings. Humanizing structures, which embody justice and community solidarity, will need to be established in a way that includes the Hutus, the Tutsi and the Twa peoples. (2)

In the four years since the tumultuous events of 1994, the efforts of peace-makers have been poured into making Rwanda once again a safe place for each of the tribes of Rwanda. This has involved the establishment of a mixed government of both Tutsi and Hutu leaders.

Neighbouring nations have gradually persuaded refugees to return to their homeland. A key part of this aspect of reconstruction has been the difficult task of disarming the power of illegal Hutu and Tutsi militias in Tanzania and Zaire (now Democratic Republic of Congo). In Tanzania administrators worked to avoid further bloodshed by setting up separate for Hutus and Tutsi. A hopeful symbol of the future was the establishment of Marongero Camp for mixed marriages, where husbands and wives and their families could settle together again before returning to Rwanda.

Before there can be reconciliation, there must be justice. For many people, justice has meant the restoration of their lives in community; the reuniting of families; the re-establishment of villages, schools, churches, hospitals, court systems, and the rebuilding of homes. The government has had to pour resources into the training of new teachers and health professionals to replace those who have been killed or exiled. Rwanda faces unprecedented economic crises as it struggles to reconstruct a society which was under-resourced before the massacres of 1994. The ongoing development of Rwanda will need to include a change in the international community’s allocation of finances and personnel. Peace within Rwanda is contingent on peace between Rwanda and her neighbours, regional cooperation and work for peace. Justice for Rwanda people includes the fair resettling of three million refugees.

Telling the Stories

In the years since 1994, one of the first steps toward reconciliation in Rwanda has been the “telling of the stories”. If approximately five hundred thousand people were killed between 1994 and 1997, it would be an understatement to say that very few people in Rwanda would now be untouched by bereavement. According to a recent UNICEF survey in one part of Rwanda, forty seven percent of children saw other children killing people, two-thirds had witnessed massacres, twenty percent witnessed rape and sexual abuse, and fifty six percent saw family members being killed. Some two thousand therapists, trained and organized by UNICEF, have been busy helping children express the horrifying scenes they have witnessed through conversation, play therapy and art. (3)

Retelling History

Another aspect of remembering has been the corporate retelling of Rwandan history. Commentators and historians are struggling to find the roots of the aggressive weed of Rwandan violence. The 1994 massacres, with their reprisals in the following years, had many precedents in the thirty years before. In the early 1960s, Tutsis were massacred in the wake of a revolution that replaced Tutsi leaders with Hutus. In 1963, between five and ten thousand Tutsi were killed. Rwanda was the home of many exiles from the 1973 and 1988 massacres of Hutus in Burundi. (4) The combined government of Rwanda now acknowledges the history of genocidal violence, along with the culture of impunity in which mass murderers were not apprehended.

The triumphalistic renderings of pre-European Rwandan history, written from the Tutsi perspective, will now need to be reexamined by Tutsi and Hutu historians together. President Pasteur Bizimungu upon the mass return of refugees to Rwanda, said, “The Rwandan people were able to live together peacefully for 600 years, and there is no reason they can’t live together in peace again.” The long-term pain of the Hutus, swept over in Bizimungu’s comment, will need to be revealed in a peaceful way before his hopes for peace can be fulfilled. (5)

Vulnerability and Responsibility

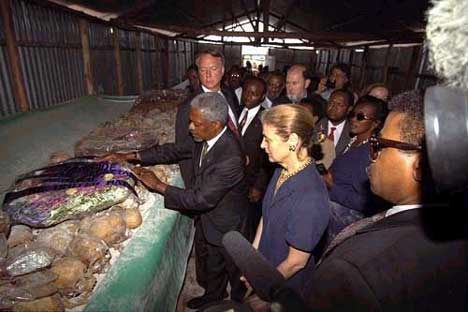

Expressions of vulnerability and responsibility are one of the keys to ongoing reconciliation in Rwanda. Visiting dignitaries have expressed their regret for the lack of action taken by the international community.

United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan, in his address to the Parliament of Rwanda, in Kigali on 7 May 1998, apologised on behalf of the United Nations, saying,

“We must and we do acknowledge that the world failed Rwanda at that time of evil. The international community and the United Nations could not muster the political will to confront it. The world must deeply repent this failure. Rwanda’s tragedy was the world’s tragedy. All of us who cared about Rwanda, all of us who witnessed its suffering, fervently wish that we could have prevented the genocide. Looking back now, we see the signs which then were not recognized. Now we know that what we did was not nearly enough – not enough to save Rwanda from itself, not enough to honour the ideals for which the United Nations exists. We will not deny that, in their greatest hour of need, the world failed the people of Rwanda.” (6)

President Clinton of the United States in March 1998 expressed the apologies of his own country and the international community.

“The international community, together with nations in Africa, must bear its share of responsibility for this tragedy, as well. We did not act quickly enough after the killing began. We should not have allowed the refugee camps to become safe haven for the killers. We did not immediately call these crimes by their rightful name: genocide. We cannot change the past. But we can and must do everything in our power to help you build a future without fear, and full of hope.” (7)

Rwanda still waits for the public expressions of repentance from those people who planned and carried out the violence of 1994. One step towards this has been the United Nations’ establishment of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, based in Arusha, Tanzania. The cases have taken a long time to process and are crippled by a lack of international provision of resources. In May 1998, Jean Kambanda, who was prime minister in the interim government during the genocide, became the first person to publicly admit charges of committing genocide and crimes against humanity. Louise Arbour, the chief prosecutor for the Rwandan and Yugoslav tribunals, said Kambanda’s guilty plea represented the most significant element of hope for reconciliation in Rwanda. “The guilty plea is not the result of any plea bargaining … There has been no agreement with respect to the appropriate sentence.” But this is not yet the expression of sorrow or regret that wounded Rwandans need to hear from one another.

Symbolic and Practical Leadership

Reconciliation requires symbolic and practical leadership, the kind that can be offered by the Christian community in Rwanda and around the world. Expressions of support and repentance have come from some quarters of the international Christian community. But the church in Rwanda seems to reflect the localized racism of the Burundi-Rwanda area. At the time of the 1994 massacre, at least sixty five percent of the Rwandan population were baptized members of the Roman Catholic Church, whose national leadership has been strongly influenced by a liberation theology in its support of Hutu dominance of Rwanda. (8) The Catholic church hierarchy was vocal against anti-Tutsi violence in 1973, and was supportive of peace talks in 1993 and 1994. (9) The Anglican church, established by CMS, has tended to have a higher percentage of Tutsi leaders. Trust in the church must have been undermined by the alleged actions of church officials who lured victims into church buildings and arranged for their destruction. Pope John Paul II has said that those Catholics who played a role in the genocide should face the consequences of their actions. (10) The response of the Rwandan churches in 1994, delayed by the fact that many of their leaders had been killed or were now in exile, needs to include public declarations of responsibility and repentance.

In the meantime, public executions take place in Rwanda, in the hope that people will be satisfied that justice is “being seen to be done”. Rwanda began its own genocide trials in December 1996, and the first defendant was convicted and sentenced to death in early 1997. (11) Like the International Criminal Tribunal, Rwanda’s government has been limited by the paucity of trained lawyers in the wake of the 1994 massacres. (12) The extent of capital punishment, seen by some as a merely a fresh horror, is described by the Rwandan government as subdued in the light of the number of people implicated in the slaughters. All the same, reconciliation and reconstruction of Rwanda society will need strong signals that the human rights of each person are respected. With the large number of accused genocidaires in prison, the Rwandan government could feel forced to move justice faster than due process would normally demand.

Symbols of Reconciliation

An important part of the reconciliation process in Rwanda is the development of appropriate symbols of reconciliation between Hutu and Tutsi. The Rwandan government in April 1998 called for week-long ceremonies and a National Remembrance Day to mark the fourth anniversary of the bloodbath carried out by Hutu extremists. In June 1996 the government, much to the annoyance of the country’s Catholic bishops, had set aside ten parish church buildings to be used as memorials for the victims of genocide. (13) The church at Ntarama, where approximately 5000 persons were killed, has now been developed and maintained as a memorial. A sign in Kinyarwanda explains that “events here should not be forgotten”. (14) A wise and healing move would be the development of memorials to victims of all sides, over a long period of time.

In their book, Towards an African Narrative Theology, Joseph Healey and Donald Sybertz explore a number of images that could be useful in the development of reconciliation in Central Africa. A Rwandan carving, in which two equal figures exchange the gift of food, is used not only as a symbol of interdependent relationships but also the model used by Jesus the king become servant. (15) They explore African proverbs and word pictures for appropriate metaphors of the reconciled church of Christ. A traditional image, the church as extended household of God, as expressed in the large extended family homestead, is symbolized in the fireplace or hearth. They refer to a proverb, “The cooking pot sits on three stones”. (16) This could well be used in Rwanda, with its three tribes. They cite the words of Bishop Obiefuna of Awka, Nigeria,

“When it comes to the crunch, it is not the Christian concept of the church as a family that prevails but rather the adage that “Blood is Thicker than Water. And by water here one can presumably include the waters of baptism.” (17)

The authors consider the potential of using blood imagery, as in the Eucharist, to symbolize the reuniting of peoples in Christ’s body.

The meeting of Christians for worship has the potential to either bring reconciliation or to bring renewed hostility. Andre Karamaga, a Rwandan theologian and Presbyterian Church leader, has reexamined the role of worship in the life of the church. “We said (after the genocide) we can no longer use worship as just a place for pastors to speak. Worship has now become a place for those who survived to speak, and for others (implicated in the violence) to confess. Worship is now a place of healing, a place for people to speak.” (18) The Easter narratives, which will always come within weeks of the anniversary of the 1994 massacres, provide powerful opportunities for a redeeming narrative for the Rwandan peoples. In the imagery of the Last Supper, the vulnerability of the suffering Jesus is reenacted. The Stations of the Cross provide a narrative of love in the midst of pain, a loving God who stays with the victims of violence and oppression. The resurrection narratives bring hope to a people bruised by death. (19)

Theology of Reconciliation

A theology of reconciliation will be a crucial element in the redevelopment of Rwanda. Andre Karamaga says that he now promotes a “theology of reconstruction” rather than the limited focus of liberation theology still followed by many Africans. (20) He has found the narrative of Nehemiah inspiring for leaders involved in the reconstruction of Rwanda.

New parables are being created specifically for fostering attitudes of reconciliation in Rwanda. Healey and Sybertz tell the story of Delphina, a Tutsi woman, and Daniel, a Hutu man. In something like Romeo and Juliet, or West Side Story, the two students meet, fall in love and plan their future together. Their families detest each other and do everything they can to discourage the relationship. They both move to Kigali to attend University and train as teachers. In 1994 the massacre hits the dormitory where Delphina is staying. She escapes to her family area, only to find that her parents, two sisters and brother have been slaughtered. Daniel’s family in turn are rounded up by the Tutsi army and massacred. He escapes to Tanzania where he eventually finds Delphina. After some time, they marry and make their way back to new Rwanda. They are stopped at the border by guards. Daniel is detained and Delphina is told to go on without him. She realizes that her life will mean nothing without his presence. She looks back to him and wonders, “Will our dream actually happen, or will it yet again be a dream deferred?” (21)

Reconciliation in Rwanda will not be an easy or overnight happening. The Christian community of Rwanda has an opportunity to be a catalyst for the telling of painful memories, providing healing and reassurance of human dignity. At this time, the Rwandan community must find alternatives to ethnic dominance and violence. The churches of Rwanda have the international and historical resources to converse with the culture of Rwanda to create new narratives of belonging and hope. With careful planning, persistence, cooperation, and creative imagination, the dream of living together in harmony could come true.

Footnotes

1. Joseph Healey and Donald Sybertz, Towards an African Narrative Theology, New York, 1996, p. 223.

2. Statistical figures for Rwanda indicated 87% Hutu, 12 % Tutsi, and 1% Twa.

3. UNICEF Website on Rwanda.

4. Elizabeth Isichei, A History of Christianity in Africa, Grand Rapids, 1995, p. 346. Between one and two hundred thousand Hutu were killed in 1973. One hundred and fifty thousand were exiled, many to Rwanda. In 1988 twenty thousand Hutu were slaughtered in Burundi. Fifty thousand were exiled. The legacy of resentment would have had a huge impact on attitudes toward power sharing with the Tutsi in Rwanda in 1994.

5. Bizimingu himself is a Hutu. The vice president, Paul Kagame, a Tutsi, led the troops of the RPF which ended the genocide in 1994.

6. United Nations Press Release, with notes on Kofi Annan’s address on 7 May, 1998.

7. Text of President Clinton’s address to genocide survivors at the airport in Kigali, Rwanda, on March 25, 1998, as provided by the White House.

8. Adrian Hastings, A History of African Christianity 1950-1975, Cambridge, 1979, p. 134.

9. Ian Linden, “The Church and Genocide”, in The Reconciliation of Peoples, ed. by Gregory Baum and Harold Wells, Maryknoll, 1997, pp. 49-53. Linden points to the complexity of the church’s involvement and opposition to the massacres.

10. Two Rwandan Catholic priests were sentenced to death in April 1998.

11. More than 125,000 people, mostly Hutus, are packed into jails and prisons around the country awaiting trial. At least 330 people have been tried on various charges relating to the genocide, and 116 have been convicted and sentenced to death. Another roughly one-third have been sentenced to life in prison. Twenty others were acquitted and the remainder received sentences of varying lengths.

12.”The predicament which the Government of Rwanda faces is not just lack of money to hire defense lawyers, though that in itself is a major problem. The most difficult part of the problem is that there are very few lawyers in private legal practice in Rwanda- sixteen to be exact. Worse still, a significant proportion of these attorneys are not prepared to assume the defense of genocide and crimes against humanity suspects because as survivors or witnesses of genocide, their memory of the atrocities is so fresh that they cannot in good conscience defend those accused of such crimes. There is no legal way of compelling these lawyers to defend genocide victims.”

13. Catholic World News, September 11 1997. The concerns of the Rwandan bishops involved not only the niceties of canon law, but also the emotional effect which memorials might carry. Church leaders worried that the memorials may emphasize only one set of victims in the tribal warfare, thereby fomenting resentments among the members of the other tribal group. The bishops pointed out that the current Tutsi-led government had spoken out against the genocidal slaughters by Hutus, without mentioning the similar killings by their own allies in the Patriotic Front for Rwanda.

14.Rudy Brueggemann, on his photographic website, describes his visit to Ntarama. “The killings here are almost inconceivable, though this was among the genocides’ smaller mass-murder sites. The brick church is approximately 50-by-20 feet in size. The small store, catechism, and two offices around the church are no larger than storage sheds. Tutsis came here for safety after Hutu extremists unleashed the bloodbath three years back. Signs of the physical violence at the Ntarama church building are still evident. The doors have been ripped off. Stained-glass windows are broken and holes punched in the walls, all presumably to kill those inside the tin-roofed building. Marc said grenades were tossed inside. Mainly, the Interahamwe and other killers used machetes to slaughter their victims. Next to the church, authorities have constructed an open-air shed containing two long tables of unidentifiable body remains. One table has victims’ skulls neatly lined in a long rows. There are about 300. The skulls show visible signs of machete blows — long cracks along the cranium. Other skulls have holes punched in by spearheads. Drying flower wreaths sit atop the skulls saying in English, Kinyarwanda, and French, “We remember you dear parents, children, brother, and sister.”

15. Healey & Sybertz, op cit, p. 109-111.

16. Ibid, p.123

17. Ibid, pp. 148-149

18. As reported by Edmund Doogue, Ecumenical News International, Geneva, May 2, 1998.

19. Schreiter deals with this possibility in The Ministry of Reconciliation, New York, 1998.

20. Ecumenical News International, Geneva, May 2, 1998. “After independence, Africans were still saying we needed to be liberated from colonialism. But colonialism was not there. The African conference of churches consulted African theologians who pointed out that “our own cultures have been destroyed [during the colonial period].”

21. Healey and Sybertz, op cit, pp. 153-156.

Hi my friend! I want to say that this post is amazing, nice written and include almost all vital infos. I’d like to see more posts like this .

I am searching to get a qualified author, long time in this area. Excellent post!