Ji Zhang was the second presenter at the Missiology and Doctrine Colloquium held in Sydney last week, speaking on “Being and Becoming the Church in the Age of Pluralism”. I wasn’t there in time to hear/see him present his paper but I had a chance to read it through. Ji Zhang is minister at Bentleigh Uniting Church in Melbourne. Ji, who comes from a Chinese background, has studied systematic theology in Australia and the USA, recently finished his PhD in comparative philosophy on the topic of unity and plurality.

Ji opened his paper with a reference to the “Faith in the Hyphen” conference held in Sydney, 2006, exploring the issues arising from cross cultural relationships in Australia. He challenged us to keep the relationship between different conversation partners a two way relationship in which wisdom is shared and received. The “hyphen” needs to be an open and indeterminate space.

Ontology is the study of the nature of being. Relational ontology, Ji explained, is differentiated from traditional ontology through its challenge of the individualism that has arisen out of a neo Platonist focus on distinctive and irreducible being. Ji took us instead to the Daoist tradition which describes a world in which everything is “inwardly connected through coming togetherness”, being and becoming together.

Ji moved on to explore “not being” – the sense of emptying oneself of definition or visibility to allow space for the emergence of the other.

Ji presented two warnings for our society, and for the Uniting Church in Australia.

1. The denial of plurality will destroy unity. This is because the elimination of the many makes the world a mere homogeneity. The “one without many” is like a human race cloned out of a single and all dominate father. The sameness will lead to degeneration, and the only result is death, because generation is no longer possible.

2. The denial of unity will result political anarchy and social chaos. This is because no binding order can be established among the plurality. The “many without the One†is like a bag of frozen vegetable in which carrots have nothing to do with beans – there is no life between them. The absolute different will also make generation impossible, because life can only come as the result of mixed identities.

Ji brought us back to the context of the “multicultural church”. Despite commitments to honour the first people and welcome the more recent people of Australia, the Uniting Church remains one of the least ethnically diverse denominations in Australia.

“We are still limited by two sociological models of multiculturalism. In a postcolonial society, multiculturalism appears to be wonderful flowers on the branches of social liberalism. From the distance it looks beautiful, but at a closer look, minority cultures are multiple petals around the social axle of some open-minded majority. Petals have no generative function apart from attract butterflies and bees to eat the sweet pollen in the middle, which eventually produces a fruit. The bottom line, of course, is power. The hangover of colonialism remains strong. Somehow the influence of Christendom still lingers over the church even after colonialism has long gone.

Postmodernism takes a negation approach towards modernity, and rejects its universalism celebrated all together. The chief argument is deconstructive. It argues the ground on which we all are standing actually is groundless. Its appearance is pluralism.”

Ji argued that we need to explore “Cross-cultural” rather than multicultural ministry, with a commitment to relationships that are bio-directional and mutual. Each culture becomes the receptacle of the others.

Our church needs to come back to the core of Christian belief and walk the path of mission where the shadow of the Cross lies. In the age of pluralism, the church needs to discover this “not-being-usâ€, which appears to us paradoxically as the Cross. Once we come to the other side of “not-being-usâ€, then we will come to realise simply yet profound truth – Christ has already been there and dwelled among them.

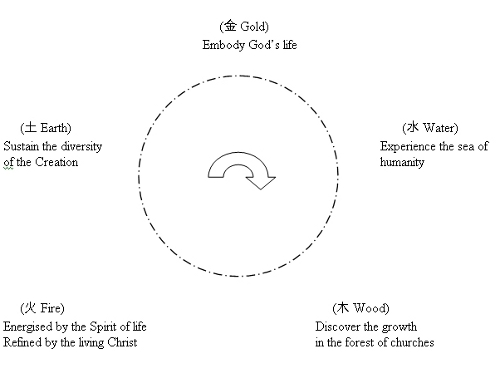

Ji finished with the Hermeneutical Circle of Mission, drawing on imagery from the Chinese tradition of alchemy.

The mission circle starts with engagement.

A) It invites people to experience the sea of humanity where riches of life can be found in the plurality of the world.

B) Turning the circle forward, it then draws people’s attention to where the growth is in the forest of churches.

C) Once the Spirit of life has been recognised, there must also be the living Christ.

D) Because the Body of Christ is defined by suffering-resurrection, the church also holds the ethical responsibility to sustain the diversity of life, voice the voiceless, and witness God’s salvation for the whole creation including the environment.

E) The circle of becoming will finally refine the gold, namely the embodiment of God’s life.

To be in God’s mission requires us to turn away from the old assumption based on the logic of causation, and free the church from the self-imposed duty of being the only lifeboat around the sinking ship of mundane life. The church’s mission can no longer be a linear advance powered by the steam of Christendom righteousness. On the contrary, missio Dei is a hermeneutical circle that animates the relational and open Being of God.

Implications

I found it helpful to be reminded that we live in a context which holds within itself a tension between disengagement (no relationship) and homogeneity (no allowance for generative change). The experience of minority ethnic groups in Australia reminds us that despite our rhetoric of being a multicultural nation, and a multicultural church, we fall short of genuine two-way engagement. Colonialism, and all the assumptions around power that goes with it, is still strong here.

I found it helpful to go right back to the assumptions at the heart of our theological traditions. Much of the early Church’s struggle with doctrinal uniformity came out of attempts to engage with the dominant paradigm of Neo Platonism. Hearing the alternative voices from traditions such as Daoism provides us with fresh ways of exploring what we mean by the mission of God, in relational terms.

It’s difficult to break out of the worldview in which we allow or require others to become assimilated into our dominant culture. This is at the heart of our reluctance to recognize new forms of Christian community outside the traditional congregation. The hyphen in Korean-Australian, for example, is assumed to feed into the dominant Australian culture, not change it. The same applies to a group of Christians who understand the ‘Church” through the lens of their Sunday morning in a sacred building led by an ordained minister.

Participating in the Missio Dei, the mission of God, will require us to empty ourselves of our self importance enough to allow for the emergence of other expressions of God’s people.

Nice to be in touch, Duncan, and I enjoyed catching up with Ji Zhang – a rare talent.

I remain busy in retirement, writing, teaching and preaching a bit, and active in the St Martin Island Community.

Remember you warmly,

Peter.